Abstract

This paper reconceptualises propositions as positional relations (topological morphisms) rather than linguistic content, and reduces hidden premises to two mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive types—Segmentation Premises and Inclusion Premises. Using a three‑storey “building” metaphor, we render classical syllogisms as compositional inclusion maps among floors, and characterise questions as continuous maps that transform the topology of this logical space. We further develop a procedural template for analysing compound noun phrases (“A of B”) and demonstrate its educational utility through a worked example. The model clarifies how meaning shifts when the lower‑level “rooms” (frames) in which a topic resides are redrawn, and suggests directions for dynamic, tool‑mediated reasoning environments.

1 Introduction

Traditional logic treats propositions as atomic sentences whose truth depends on explicit premises. Yet many argumentative failures originate in implicit premises whose structure remains opaque. We contend that these premises can be fully characterised by only two operations—cutting and containing—and that reasoning itself is best visualised as motion within a constructed space. Our contributions are:

- A proof‑sketch that all premises reduce to segmentation or inclusion.

- A geometric interpretation of the syllogism as chained inclusions across building floors.

- A definition of questioning as a topological transformation.

- A step‑by‑step template for analysing “A of B” propositions.

2 The Bipartite Premise Model

| Type | Formal Operation | Function | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Segmentation Premise | Partition U into A ∪ ¬A (law of excluded middle) | Fixes definitions, “draws walls” | AI vs. non‑AI |

| Inclusion Premise | Map A ⊆ B (or A → B) | Frames a topic within a broader context | AI ⊆ labour‑saving technology |

All causal, functional, normative and institutional claims are specialisations of inclusion; all definitional moves are specialisations of segmentation. Together they are both mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive for meaning construction.

3 Architecture of Reasoning

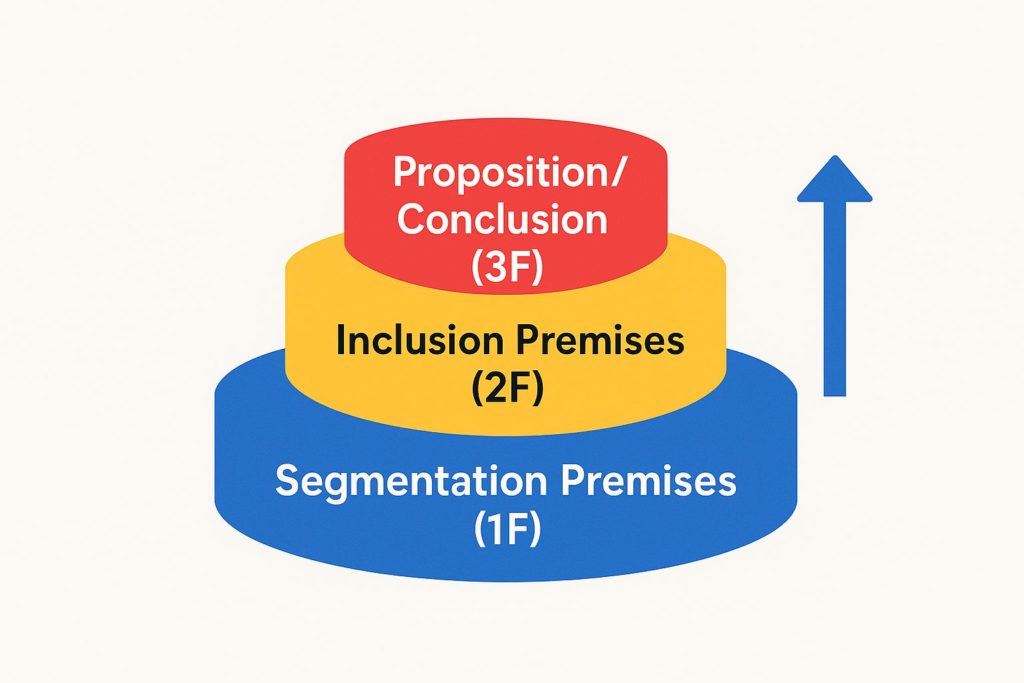

3.1 Three‑Storey Building

- Ground floor (1F) – Segmentation rooms (widest floor area)

- Second floor (2F) – Inclusion rooms (narrower)

- Third floor (3F) – Particular conclusion (narrowest)

3.2 Syllogism as Inclusion Composition

2F ⊆ 1F (major premise)

3F ⊆ 2F (minor premise)

───────────────

3F ⊆ 1F (conclusion)

Example:

Major “All humans (2F) are mortal (1F).”

Minor “Socrates (3F) is human (2F).”

Therefore “Socrates (3F) is mortal (1F).”

The walls (inclusions) themselves are the propositions; floors are merely loci.

4 Questions as Topological Transformations

A question q acts as a continuous map q: ⟨U,τ⟩⟶⟨U′,τ′⟩q:\; \langle U,\tau\rangle \longrightarrow \langle U’,\tau’\rangle

that either

- Refines a partition (redraws walls) or

- Reframes an inclusion (moves a room to a different wing).

Dynamic Example—Reframing AI:

Before : AI ⊆ efficiency tools

Question : “For whose efficiency?”

After : AI ⊆ surveillance infrastructure

Thus inquiry is not external commentary but spatial deformation of the logical edifice.

5 Template for Compound Noun Propositions (“A of B”)

Step 1 Parse

“Art is an expression (B) of sensibility (A).”

Step 2 Individually re‑segment A and B

| Component | Default room | Alternative room (illustrative) |

|---|---|---|

| Sensibility (A) | Inner aesthetic feeling | Socially conditioned affect |

| Expression (B) | Self‑revelation | Institutional display |

Step 3 Re‑compose a single inclusion

“Art ⊆ institutional display of socially conditioned affect.”

Step 4 Compare semantic shift

The locus of evaluation moves from personal authenticity to socio‑political instrumentation.

6 Discussion

- Pedagogical value: Spatial metaphors and stepwise templates facilitate novice grasp of hidden premises.

- Completeness claim: While a formal proof is pending, we argue that any premise must either delineate a class or locate a class within another—no third alternative exists.

- Dynamic tooling: A visual reasoning environment could log question‑induced deformations as a time‑stamped sequence of topological maps.

7 Conclusion

By treating premises as architectural operations and propositions as inclusion morphisms, we unify static logical analysis with dynamic interrogative practice. The resulting framework offers a transparent method for uncovering implicit assumptions and demonstrates how asking the right question literally “moves the walls” of our conceptual space.

References

Aristotle. Prior Analytics.

Peirce, C. S. “On the Algebra of Logic.” American Journal of Mathematics 7 (1885): 180–202.

Lakoff, G. Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things. University of Chicago Press, 1987.